Born in 1945, Denny was raised in Iowa by an adoring family. He and his older brother were good pals. Both parents were employed, his father by the railroad and his mother with the local dentist. Denny was no stranger to the military. Two of his uncles had served, as well as three cousins. His great-grandfather was in the Civil War. He treasured the box of their old Navy and Army patches and other military memorabilia.

Denny thrived in high school and excelled in sports, including football, basketball, baseball, and track. He especially enjoyed the camaraderie with fellow teammates. During his sophomore year, ROTC was mandatory. This would be his first direct military experience. He spent many summers on his uncle’s ranch in Colorado, where he developed a love for animals.

In 1963, Denny graduated high school and married his first wife. He attended college in Colorado to pursue a degree in premed veterinary medicine. Due to red-tape issues with residency, Denny became discouraged and moved back to Missouri.

By the beginning of 1965, US combat units were deployed to Vietnam. Denny was drafted in 1968 at the age of twenty-two. He served in Vietnam for the better part of his two years in service. Although he was initially trained as a radio operator, his primary role became infantry and reconnaissance in the 75th Infantry. He is the recipient of three Bronze Star Medals.

When he returned home in 1970, his marriage was on the rocks. He began working for the railroad. Soon after, he met and married Sandy, his second wife. Over the years, they settled in California and started their own company, but Denny was tormented with anger, inexplicable outbursts, and health problems. In 2008, they visited the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, in Washington, DC, in remembrance of twenty-three brothers killed in action and to seek some closure. Everything unraveled. Denny knew he could no longer “keep the lid on his box of stuff” and that he needed to seek professional help.

Finally, after learning about the post-traumatic stress that had caused him nearly forty years of anguish, he found relief with the solid foundation of support from his wife and two sons, and the partnership with his service dog Abbey.

EXCERPTS FROM OUR CONVERSATION

Vicki Topaz: By 1968, the draft was in full force. What was that like for you?

Denny McLaughlin: Every day I’d go home, look in the mailbox, and hold my breath. One day in April 1968 there was the brown envelope, and I had to report to Kansas City for induction. I was drafted. I went to Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri.

When you received the brown envelope, what were you thinking?

It was dealing with the unknown, and it was knowing what the percentages were that you’d be going to Vietnam at one point or another, regardless. When you go to boot camp, you don’t know what school they’re going to put you in as a draftee. If you enlist, you can request a couple of options for schooling. With the draft, you go where they tell you to go.

I was about twenty-three, older than the boys. I was older than my company commander in basic training. That was a whole new role for me because I’d been out on my own since I was seventeen. It was a big change socially to have to march in line, shave off all my hair, and wear these funny clothes. Unless it’s time for you go to your bunk at night, you can’t get caught lying on it during the day. It was a big change, the resocialization process from civilian to military.

So that must have meant a change in the marriage as well.

Yeah, it had an effect on my marriage. I don’t doubt that. Out of the two years I served, I was only home maybe forty-five days. I went from basic training right on to advanced training, with a visit home for two weeks, and then to Vietnam.

Where was the advanced training?

That was in Fort Huachuca, Arizona. I was trained as an intermediate speed radio operator.How long were you there?

Did you ask for that?

You do a battery of tests, and then you do eight weeks of basic training. They go through some of the most ridiculous tests for aptitude. Then you get questions like, “Do you like camping?” “Do you like the outdoors?” “Do you consider yourself the he-man type?” After about the third question, I said, “I know where this is going.”

They sent a group of us to take another battery of tests that turned out to be for OCS—Officer Candidate School. A recruiting sergeant called me in and said, “Well, you’ve qualified for OCS, and we think it’d be a really great opportunity.” He was pushing me to make the military a career. He said I’d have about $300 a month retirement, which sounded like a lot of money.

I told him, “You know, I’m a draftee. If I went to OCS, how would it affect the two years of active duty?” He said, “You would have to reenlist to cover that extra year of OCS.” I said, “You know, I don’t think I’m interested in that.” It got to where he actually got upset with me. At that point, I didn’t want to spend an extra year in the military, so I went back to the barracks and went on to basic training.

Typical LRRP team.

Back to your training as a radio operator . . .

I spent a lot of time learning how to tune radios and a lot of time on Morse code. You spent time in the lab sending and receiving coded messages. In our class, if you could proficiently work twenty-five word groups a minute, after ten weeks they would send you to Fort Gordon, Georgia, to teletype school. I qualified for that, along with two other fellows. We never got orders for teletype. So we continued three weeks of school with about six people living in a big barracks together. I don’t know if it was a mix-up or what. At the end of the thirteen weeks, we got our orders for Vietnam. A week of our normal leave time was spent on RV training.

“RV” stands for what?

Republic of Vietnam. We were off in a wooded area in the mountains of Fort Huachuca, where it’s just like the jungle. They had a mocked-up village with trap doors, ambushes on mountain roads, and all. They had us firing M16s, which I’d never had in my hands until then. We did three days of shooting and qualifications, and then we were finished with that training.

I went home for two weeks and then went to the Oakland Army Base to be processed. I was there for three days in a big, hangarlike warehouse, restricted. You couldn’t leave until you had orders. They held you captive, so by the time you finally got called for a flight out of Travis Air Force Base with orders, you were excited.

By the time you got to Oakland, did you feel like you’d had adequate training?

I was well trained in my MOS—my military occupational specialty—which was A05B Radio Operator. This soon became secondary to my new MOS 11 Bravo 20, Light Arms Infantry. You get initial orders and it just says APO—Army Post Office—in some city that you can’t pronounce. Mine said Quang Nam, located up north on the coast of South Vietnam, so I assumed that’s where I was going. You get these orders and you go. I went to a replacement center in Bien Hoa Air Base.

We flew into Bien Hoa just outside of Saigon, and we were bused over to a replacement center in Long Binh. For three days we were doing everything—burning human waste, the whole nine yards—and getting used to the heat. We had no idea where we were going. They were shipping people all over the country. One morning, my name was called. The sergeant said, “Get your stuff loaded on that deuce-and-a-half truck—you’re going to 1st Infantry Division.”

Did you know what that meant?

I thought, “I’m going to be the radio operator somewhere in the hierarchy of the 1st Infantry Division, which was a big division.” We went to another processing station, where about eight of us were assigned to the long-range reconnaissance patrol—or LRRP. Now up until then, that had been all voluntary, but they were running short of people.

We were sent over to the airstrip to be flown up to the rear headquarters in Lai Khe. Seven of us were radio operators, and the other person was either a clerk typist or a supply clerk, so getting onto that airplane didn’t mean anything to me. The last thing the guy that was doing the shipping manifest said to us as we were getting on the airplane was, “Well, boys, you better just kiss your ass goodbye. You’re going to a LRRP company.” That was kind of an odd comment, but I didn’t realize I had anything to worry about. I mean, I’m a radio operator—I’m going to sit and run the radio.

We fly into a short airstrip cut out of the middle of a jungle in a C-121. We get out the back, and there’s a young sergeant waiting for us with a truck. He greeted us and said, “You’re going to the north company. We’re on the other side of the airstrip down by the perimeter, and we’ll go over there in a minute. The first thing I want to do is buy you guys a beer—because you’re going to need it. You’re not going to have much pleasure where you’re going.”

But I’m a radio operator, so I’m not too worried about it. We go into this small company, divided by a dirt road. First platoon was over here, second platoon over there. The orderly room or the commander’s office and the first sergeant had a tent. Our wood-frame tents were on one side, and we had kind of a company area across the street.

This huge Latino first sergeant steps out, I mean big. He had bad names for us troops, and everybody was looking up at him and scared to death. He started laying out some of the ground rules. And then he said, “You’ll all be assigned to reconnaissance teams in the morning.”

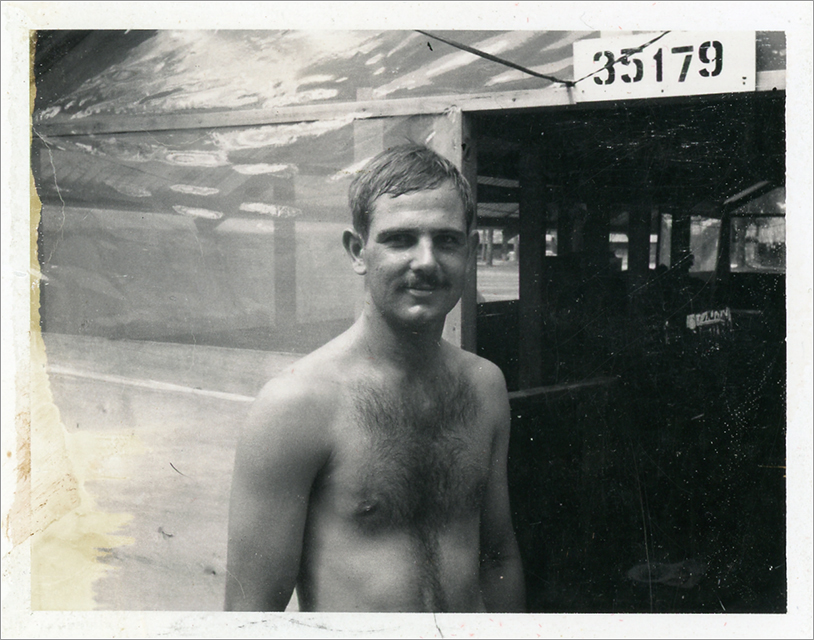

Goofing off in company area.

We were assigned to different tents, which we called hooches. Three of us ended up in the same tent. We got jungle fatigues that were so different from the fatigues in the States. We’re putting stuff away and wondering just what exactly we’re in for. I don’t see a radio anywhere.

We all got M16s and twenty magazines. We were told to keep them at the ready at all times. We put together our load-bearing gear: ammo, hand grenades, and rucksacks to carry other stuff in. That ended up being the first team I was on. We met our team leader, Francis Keller, and his assistant team leader, Don Hildebrand. The very next morning, our team was finalized, with six men living together.

We immediately started learning to do escape-and-evasion drills, along with our responsibilities, which depended on our position in the line of march. We had a point man. We had a team leader and usually a scout and a radio operator. If you were five or six guys, you had a radio operator and rear security. The point man has a 180-degree responsibility to the front. The team leader takes 180 to the left, and the next guy 180 to the right, rotating back and forth when we’re on escape and evasion. Then if the point man gets into contact, he fires and rotates back. The next guy fires a magazine, and they keep rotating back until we’re leaving the area if we need to. We practiced or ran the whole time we were in base camp. That was standard procedure.

We started learning surveillance techniques and how to move without making noise, using hand signals. I got ready to go on my training mission. This was enemy territory, what we called “Indian territory”—which was anything outside the gate.

I’d get all loaded up and put on the camouflage paint. I had the PRC-25 field radio in my rucksack, three extra batteries, smoke grenades, and hand grenades. Very little room for food. I soon learned that I needed to replace all the heavy food with water because the two main things to survive in the jungle are ammunition and water. Sometimes one is more important than the other. I started to readjust my thinking.

There was a little village on the edge of our base camp where I would buy Vietnamese baguettes. If it was going to be a one-week to two-week mission, I’d get three of those and C-rations. And I’d take little cans of boned turkey or chicken because they didn’t take up much room or weigh much. So a can of that and maybe a third of the baguette made my meal for the day. With all the heat and being in that setting, you don’t really get hungry.

On my first mission, it had just gotten dark and an AK-47 went off. I found out later it was a signal round, somebody signaling that there are Americans in the area. I about crawled out of my skin. It scared me to death. You stay tense for three or four days. When you finally come back to base camp and the adrenalin comes down, you hit bottom. You sit on your bunk, you’re unshaven, you’re dirty.

You can’t even use mosquito repellant in the jungle if you’re trying to hide, because of the smell. There’s absolutely no smoking, no anything out there. Sometimes, you don’t say anything, even to a man next to you for five, six days at a time. It’s all done with hand signals. We’d take turns taking naps in the afternoon because we were up most of the night. We would form a tight 360—what we called the “wagon wheel,” where you lay in a circle, with everybody’s boots touching in the hub. When you go to 50 percent security, half the guys are resting, and the other guys are keeping watch. You tap the next guy on the leg when it’s time for him to take over. You learn a lot of little things on the job.

Were nights the most vulnerable times?

You were always vulnerable, but nights were bad because sound is amplified, especially during the monsoon season. You’re standing out in a triple-canopy jungle—with vegetation growing at three levels—and a drop of water would fall and cause two more drops to fall. And you’re sitting there in the darkness, listening. Usually, you don’t even get much sunlight. Your mind’s telling you that there’s a battalion coming your way because that’s what it sounds like. Or you run into a swarm of termites that eat a path for themselves, chomping—you can hear them coming. Or you hear a rooster crow. You think, well, we’re in a free-fire zone, we’re out in the middle of nowhere . . . But when a rooster crows or a dog barks, it tells us we’re close to something we need to focus on.

Dirt road through middle of our company area, Lai Khe, Vietnam.

It’s a daily thing. The object of long-range reconnaissance is to go out, do missions, and not be seen or heard. Get in, get out, share the information. It doesn’t always happen that way.

You go in by helicopter most of the time, so obviously somebody’s going to hear that if they’re in the area. Usually, when we would get into a situation—they call it “being compromised”—it’s like they know we’re there. They see us, and we can’t do anything about it. Or they try to ambush us, and then we get into a firefight. We initially carried enough armaments, but not enough to sustain a long firefight. We did whatever was needed to protect ourselves and then figured out how we were going to do the escape and evasion without running into more trouble. And it was tense being in a base camp because we got rocket fire every night.

Several times they extended us for a week. We’d run out of food and water. One of my worse triggers is heat. Once they gave us a certain grid number on a map where there’s a stream to refill canteens. We got over there and found that the stream was dry. So we were redirected to another grid. That stream was dry, too. They finally gave up and said, “You guys need to walk in, you’re only four klicks—kilometers—from the base camp edge.”

We had to go across a big area that had been row-plowed the year before. That’s where they take two Caterpillars and run a huge chain between them, and they knock everything down to clear a site. The next year it all grows over, including bomb craters. It looks like a field of corn that’s been processed. You walk along, you fall in the bomb crater with your gear, you have to climb out, and the sun’s beating down on you. There’s no shade, no water.

Out in the middle of it, there’s this little old sapling tree that had a tiny bit of shade. We had two guys down, probably with heat stroke. You get to the point where you’re so tired, so hot that you don’t think you can take another step. I felt like if they walked up and slapped me to death, so be it. After we had covered half the distance, they finally sent out a small squad from a mechanized unit—a tank and two armored personnel carriers—to pick us up. They gave us water and cold towels and took us back to the company area. And that kind of went on and on.

Then in April of 1969, I went on R & R and met my first wife in Honolulu, but it was “no there, there.” I don’t know whether it was just me being used to living as an animal or her being different because I had been gone. It’s crazy to say it, but I actually looked forward to getting on Pan Am and going back to Vietnam, going back to my buds.

One of my best friends was killed the day before I got back. I felt bad because he was getting ready to go home, and he shouldn’t have been out there. If I’d have been in base camp, I would have gone in his place. It was one of those things that rattle around in your head. Through the year you’d go out, report, come back—with no action and then finally a lot of action. Somebody gets killed.

This went on daily. We did a lot of running in the morning to stay in shape for the heat. I drank a lot of beer in the evenings and played a lot of music. We came to have a standing rule that thirty days before you’d go home, they take you off the team and you’d just stand down, get ready to go back to the United States. My buddy that was killed while I was on R & R had had only two and a half weeks left. He shouldn’t have been out there.

You are the recipient of three Bronze Star Medals. Could you describe those experiences?

It’s hard to tell you how I got the Bronze Stars, what I was doing when I got them. I spent a year running around being scared to death most of the time after that first encounter when we had a firefight and were being shot at and also shooting someone. You know, when you’re growing up, that’s not what you learn to do. I had a hard time with that. I wrote a letter to my mother to explain how I felt, how things had happened so fast. I honestly could not see how I was going to survive a year.

One Bronze Star was for action on December 1st, 1968. We were supposed to be on a simple reconnaissance mission. We weren’t that far from the base camp—the main idea was to keep an eye on things. We were in an area that had a lot of bomb craters, and the greenery had been knocked down after being sprayed with Agent Orange. We had to be careful not to fall in the bomb craters.

Then we started hearing the Vietnamese language. We kept hearing a voice, but we couldn’t locate it. This went on for quite a while until we looked up and saw a Vietnamese spotter standing on an old tree trunk. He immediately started firing at us, and they began laying down mortars that started exploding around us. Everything happened fast. A black kid with us was unconscious from heat exhaustion, so I threw my body over him because he wasn’t able to defend himself. It was probably another hour before we could get gunship support, enough to get a medivac helicopter in. Then we used that same fallen tree to get high enough that the helicopter could hover and we could stand up on the log and hand the guy up to the helicopter. They eventually came back and took us out in a helicopter.

You know, you don’t do things like that for recognition. I was surprised that several of us got awards for that day, but somebody wrote it up. That soldier recovered, and nobody was seriously injured.

Lt. Davis and me with my stolen Vietnamese fireman’s hat.

You didn’t think you would last the year?

Right. It’s like, Do I really want to be close friends with this person? Because he could be gone tomorrow, I could be gone tomorrow. You’re living with that constantly. Sometimes, you’re having a good time, and people are laughing—after something frightening happens, people are kind of giddy. They’re not really happy or excited—they’re trying to overcome being scared to death.

There was nothing pretty about it. There are things that stick in my mind when I tell people about the sweet smell of blood. When you crawl into a helicopter that’s been running back and forth with wounded people, and the blood is starting to dry on the metal parts, the blood has a sweet smell to it . . . You have three or four people’s blood on your hands. It’s dangerous work. I think, in reality, if a person is in a war zone it doesn’t matter if they were in the infantry. There was nowhere safe in-country. They had bombings in Saigon, and even people with soft jobs weren’t safe.

Describe the time when you were under a tree and two of your squad helped you out.

Four teams went out. They took a big area and broke it into four sections. You come in on helicopters about four to six feet off the ground, and you start jumping out of them. The helicopter pilot touches the ground and leaves real quick so he’s not a target. We would go to the tree line for cover and sit for fifteen minutes until the helicopter was out of the area. Then we would start the mission. We found a trail with a hot cigarette butt on it. We knew this is going to be a problem because there was supposed to be enemy in this area. We didn’t go much farther. We heard voices and found holes where the enemy were burying ammunition or food. Eventually, we heard a generator out in the middle of nowhere.

The craziest thing about it was there was a fairly good-sized tree that had branches that almost touched the ground. We heard voices coming our way. I think there were only five of us. We hid under that tree. I was on my knees, and I had the weight of the radio. These people would come up near us, yakking. They’d come up and they’d leave, they’d come up and they’d leave. You could hear them digging . . . Finally, our team leader took out a grenade. He pulled the pin and was about to throw it, but they walked away, and he put the pin back in the grenade. This happened maybe three times. He said, “They’re coming, and it looks like they’re going to come all the way to the tree this time.” He was ready to throw the grenade. I had an M72 LAW antitank rocket I was getting ready to fire, and then my legs went to sleep. I said, “Guys, I got a problem.”

We called for helicopters, and they were going to try to pick us up. I got clear over on my elbows, and the guys pulled my legs out and rubbed them. They asked, “Are you ready yet?” I said, “Yeah, I think I can go.” By that time the guy was standing there looking through the tree limbs looking right at us, and he got all excited, so we tried to make an escape and evasion off to the side. While we’re running to the edge of this clearing, they’re trying to flank us and come in from behind.

Finally, the gunships got there to try and help us. When the helicopter finally came in, everybody took turns: one guy would run, and the other guys would cover. I was the last man to leave covered, but I was the first one to dive into that helicopter. I remember picking up empty magazines that had fallen out of my shirt before the next guy even got there. I was carrying all this weight, I was all pumped up, and I had run right past him.

The sad part of this story is the very next day they put two teams back in that same area on the exact same LZ—landing zone—that we went in on.

They never got off the LZ, and only one guy survived out of the six. The shell hit the signal mirror in his pocket, and he lay there faking being dead. He was the only survivor. You’re trying to figure out what the military thinking was? That incident caused an uprising in our company area because the company commander—who nobody cared for—wasn’t experienced in this type of military work. He’d been a general’s aide. He was down in Saigon, and he didn’t come back after the first day of a series of missions where all these sightings were. One team counted 300 and some-odd enemy, and that was probably an undercount. It developed into a major battle for the whole division. They brought in big units. It’s listed in history as one of the big battles of The Big Red One—which is what the 1st Infantry Division is called.

You’re seeing guys wounded, and you’re trying to treat the wounded, and you’re trying to protect yourselves. In February, Bobby Law—Robert Law—earned the Medal of Honor for saving his buddies by throwing himself on a grenade. We were out in the area of operations, and they were the next team over in another area. We heard the grenade go off, but we were too far away when the firefight started. We couldn’t get there fast enough to help.

Did you sustain any injuries in-country?

A couple of things: I had my right eardrum almost blown out. A team leader had leaned on my shoulder and used it for a brace while he fired a whole magazine next to my ear. I lost my hearing for three or four days. We had been hiding behind a termite mound that we were using as a shield because we had called in an artillery assault. I had carried the radio, but I had to give the headset to my team leader because I could not hear a thing. I remember setting down my rucksack and gear, and one of my commanding officers, who is a good friend to this day, took me over to the aid station. I don’t know what they gave me, but it knocked me out. When I woke up the next morning, they had moved an entire artillery unit in overnight. They had lifted them in with the big helicopters.

LRRP teams waiting to depart on various missions.

I was taken out of the field for a week. After that, I had to be very careful of what types of missions that I was going to be involved with because I was afraid I wouldn’t hear something. That was a deal changer.

Also, one thing that I didn’t document was when I jumped out of a helicopter and hit my elbow on the skids. I think at the time, with the adrenalin flowing, you just neglect reporting it. Now in the last ten years it’s come back to bite me. It led to us having to sell our small manufacturing company because I wasn’t able to continue working due to that injury. Indirectly, that has a lot to do with staying in denial as long as I did, being able to keep everything “squashed down.”

Your service ended in 1970. What was your experience on reentering the USA?

I got back around ten o’clock in the morning at Travis, and then they bused us to Oakland. I spent the night in Oakland and went over to San Francisco the next morning. I got off the bus and walked over to TWA. A large group was there.

Were you in uniform?

Yes, I had traveled in uniform. Two or three people were shouting at me, and this and that. I just tunneled it out. I walked to the counter and got my ticket and went in. There wasn’t the security stuff to go through that we have now. I walked in thinking, “I don’t dare stop—I’ll take somebody out.” I probably had steam coming out of my ears. I checked in and went over to a little bar by my gate to have a beer and settle down. The nicest older lady was sitting at the table and she said, “You can join me.” She paid for my beer. So by the time I got on the airplane, I was still pissed but not as bad. I got to Kansas City and went home.

How was the homecoming itself?

I was just glad to be home. There wasn’t a lot of rah-rah with the wife, but I enjoyed her mom and dad, who I was very close to. When you come home, you’re thrust back into a life, and you don’t really know how to react to things and noises.

Did you feel welcomed when you got back home?

Yes, there was a small group. My brother-in-law and I married sisters, and their family was excited. By then, my mom and dad had moved back to Iowa. I was just trying to get settled down, not knowing where I was going to get orders to next. I wasn’t getting too comfortable, because I wasn’t done yet with the Army.

The very first day, my wife told me she wanted a divorce. I hadn’t even taken my uniform jacket off. I was just starting to unloosen my tie when she said, “We need to talk.” At that time, I had such a mixed bag of emotions—being extremely mad, hurt, not believing it. And then never having gone through that before, I couldn’t imagine what would happen next.

You came home with certain expectations.

I wanted to get back to normal life. I had turned twenty-five and I knew that I could not stay in the same town, because I was working myself to death. I was paying my wife’s debts, working at the packing house about sixty-five to seventy hours a week. I just thought, I can’t do this. I drove up to Iowa over the weekend to visit my folks, and I told my dad I didn’t know what I was going to do. He told me that the railroad was hiring. We went down to the depot and talked to the agent, and I was hired on the spot.

Were they happy to be hiring a veteran?

I don’t think that even entered into it. They needed bodies. Typically, there wasn’t any advantage to being a veteran. A lot of the guys on the railroad were veterans who were working the job during the war handling critical supplies.

So in the summer of 1970, I was working as a brakeman on a freight train. After I’d get home, I’d be on another train going somewhere within the next eight hours.

That fall, Sandy’s dad and her sister came over to visit. Sandy and I had grown up together. I’d known Sandy since she was a little scoot. She’s four years younger than me. She and I hit it off. We got engaged around Thanksgiving, and in May 1971 we got married.

So you had been out of the service for a little over a year by then. Life was moving along.

Yes, it was moving along. In one way I felt a numbness, but I had this new life, and it was helping me override that feeling. We came out to California in December because Sandy’s grandmother couldn’t make it to the wedding. She sent us tickets to come visit. I loved it. In the service I didn’t see much of California except for the drive up to Travis Air Base. We were talking one day and decided we could find jobs. So we stayed in San Jose. We didn’t go home for a year.

Sandy found a teaching job, and I went to work for the FMC canning division. Eventually, I got a job working for Levin Metals Corp., helping them establish their precious metals program. And that’s where I started my career in precious metals.

Special Forces Recondo School, Nha Trang, Vietnam.

When does the war experience start processing through your mind, through your emotions? Are you ever able to let it go?

I don’t think I’ll ever let it go. I can’t get through a day without something reminding me. I’ll read something, I’ll see something, I’ll feel something, or I’ll smell something that takes me back.

Tell me more about your life and getting established out here.

We were building a new life together. But I always had anger issues. I’ve had to replace shirts where the buttons had been torn off. Neckties ripped up. I’ve replaced sheetrock. There was always the possibility of going off.

I was in denial, and I stayed there a long time. I had anger issues, and they were not predictable. I never hit anybody. I’ve never hit Sandy. I just never knew when somebody would do something stupid that would make me go off.

You could see that about yourself?

I just don’t tolerate somebody doing something stupid, or messing up, or making my job harder. That carried on clear up to when I left precious metals after eighteen years.

During this time, were you going to the Veterans Affairs hospital for any physical problems?

I was having back problems. This was when we were still living in Gilroy in 1992, and we didn’t have health care. Sandy called the VA, and the guy said, “Absolutely, he can come to the walk-in clinic.” We’d never been to the VA. Never given it a thought. It was a stigma, going to the VA. You’re getting a handout, you’re getting help . . . I could barely walk through the parking lot to get to the entrance. A doctor sent me upstairs to get X-rays, then I saw a specialist.

Did you know the VA was available to you?

Yes and no. While I was there, a young guy asked, “You’re the Vietnam veteran?” He asked if I’d signed up for the Agent Orange screening process. It was in the early 1990s before they even started recognizing Agent Orange. So I got signed up. About a week later, I did my whole screening physical.

What did the Agent Orange screening consist of?

It’s a lot of blood tests and checking mobility. Back then, only two diseases were recognized for Agent Orange. But I just got my latest bulletin from the VA, and now there are fourteen related diseases. One of the first diseases they recognized was spina bifida in offspring.

When I got back from Vietnam, I had problems with my feet and bouts with malaria. We knew what it was but didn’t go for help, because I thought, Well, I got it in the jungle and now I have it. The injury’s not documented, though. I outgrew the malaria reactions, and the problems with my feet finally cleared up.

What happened to your feet?

Basically jungle rot. If you’ve waded through water or you couldn’t take your boots and socks off for a week at a time, that can do it. I was so glad about not being in the Army anymore that I tended to overlook the elbow and the feet. But even to this day, I still feel like I’m a walking time bomb. For example, I have severe nerve damage, and I find myself wondering if that’s related. So there’s a lot that’s hanging out there. It’s like waiting for the other shoe to drop. I hope it never does.

When did you first learn about post-traumatic stress?

I started hearing about it in the early 1990s, especially when we got into the VA system. In 1994, I got active in the Veterans of Foreign Wars, and some of the guys my age or younger were saying, “You know, you need to get checked for PTSD.” I was in denial: “It can happen to all you guys, but it’s not going to happen to me.” There was a connotation that if you got PTSD, then you’re seeing a psychiatrist, or you’re in that group in medical care. If you’re getting mental health care, you’re crazy, you’re mentally ill. It always had a stigma attached to it.

Memorial service for LRRP team KIA November 1968.

Did that keep you from asking for help?

Of course. I was in denial. And when I started feeling the anger and getting depressed, it drove me further into denial. I buried myself in work. In later years, I’d come home worn out because of overwork. But outside of work, I’d get depressed, feeling bad about my self-esteem. It comes at you in different ways.

Then there were a number of occasions with my temper and kind of acting out, and I wasn’t so friendly. When your peers start recognizing issues—like the guys I’d served with and even in the workplace—and say, “You probably need to be checked out,” I told myself I was all right. It was everybody else—they’re the ones who didn’t have what it took to man up and deal with it.

I was raised that way. You don’t whine about things. Jobs are hard. You just put your nose to the grindstone and keep going. You don’t complain. I think that attitude helped me survive two years of military. Into the 2000s, it got worse with some uncontrollable things, like hitting sheetrock, slamming doors, breaking windows. Things just didn’t work out right.

You had triggers.

I did. It could get too hot and I’d almost pass out. I’d have to go sit down. Or I would smell something, or hear a noise or airplanes flying over.

And when you’re dealing with the electronics industry, you’re dealing with all kinds of different people. Some are more hardheaded than others. It was getting worse. Then—I can’t remember what led up to it, but we had this small manufacturing company in Hollister, and I ended up unable to physically work there anymore.

In June 1990, we had to close the doors. Financially, we lost everything, and we were in the process of losing our house in Gilroy, so we had to scramble around. In 1991, I had an opportunity with a manufacturer of plating racks. A little later, in 1994, Sandy and I were able to buy the company, which we maintained until I started having physical problems.

What were these physical problems?

I would walk through my shop with a screwdriver in my hand, and when I was ready to use it, I’d raise my hand and see that it had fallen out of my fingers without me knowing it. The problem’s from the old elbow injury in a helicopter. I have nerve damage. I’ve had a couple of surgeries on the elbow and a couple on the wrist. On a good day, I’m about 65 percent with my left hand. The VA botched the surgery the first time.

What was the origin of that injury?

Going through the trauma and the experiences, there’s a lot that I mentally blocked out. I would have nightmares about the blades of the helicopter hitting tree limbs. I was having night terrors every once in a while over that.

After we got back, one of my commanding officers came over. We were just visiting that afternoon . . . He said, “While I’m thinking about it, I have some information from a helicopter pilot. It’s a copy of what happened the day our helicopter crashed.” I remember telling him I wasn’t in a helicopter. But he said, “You were. You were with me.” He gave me a copy of the after-action evaluation of the pilot.

We were compromised out on patrol, so a helicopter came in to get us on that small LZ. They didn’t want to leave anybody on the ground. It was so hot out there . . .They wanted all of us to go, but we were overloaded . . .

The chopper went down through the trees, and when it hit, my elbow hit the skid as I was getting out. That’s how Jerry Davis, my Lieutenant, remembered it. I just don’t remember being in the helicopter except for the night terrors, or that I had hit my elbow. And at the time, you don’t remember about your aches and pains, because other guys were hurt a lot worse.

When I talked to the surgeon, he asked if I’d ever hit my elbow really hard. The only thing I could think of was hitting my elbow on the skid as I was going out the door of the helicopter, in full gear. But because nothing was documented, I can’t prove it.

Company Commander Lt. Patrick, KIA May 1969.

Tell me about your trip to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial.

Sandy and I had the opportunity to go to Washington, DC. We were going to look at the Smithsonian, and Sandy kept asking when were we going to the Wall. I kept saying, “Well, we’ll do it tomorrow.” I wanted to go there, but I didn’t want to go there. We ended up going on our last day in DC. We looked at the names of my twenty-three brothers on the Wall, and I told her the stories behind each death.

I sat down on a bench in the shade because it was getting warm. I had a clear view across the lawn, looking at the Wall . . . And I just melted. I fell apart. It was like the sea had parted. Luckily, there was hardly anyone around. I cried twenty, thirty minutes. I just shook and I couldn’t grasp it. I knew a small segment of the over 58,000 names. It just zapped me.

Reflecting back on it, I realized then that I did have an issue that I couldn’t wrap my arms around, because I’d stayed in denial so long. After visiting the Wall, I knew I needed to get help—but I was still afraid to do it, because of that stigma about mental illness. I struggled from that fall visit clear up until January 2009, when I went to the VA for help one cloudy afternoon.

Sandy, you were with Denny at the Wall, and you went through this experience with him. What was that like for you?

Sandy McLaughlin: I felt like I needed to call 911. I’d never seen such emotion. I didn’t know how to soothe him. It was so deep. He was just so broken and so sad as he told me stories that I hadn’t heard. I had no idea of the terror and the details of sticking guys’ guts back in and putting them on the helicopters, with blood everywhere. He’d never ever told me those things. I had no idea.

So it was your first glimpse into his actual war experience?

S: I thought his anger was because he wants to be in control of everything. But this was such sadness and remorse, and he kept saying, “It’s such a waste, these wasted lives.” There’s nothing you can say to that. It broke my heart to see him so broken. After facing the Wall, there was no escape.

D: It was mid-January 2009. I was up for a normal medical checkup because back then they were seeing me about four times a year because of Agent Orange. You go in, they take your vital signs, and they ask you what your pain level is that day. On this visit, a nurse asked, “In general, how are you feeling today?” I don’t know what made me let the words come out of my mouth that day, but I said, “I don’t feel right. I’ve got something going on.” She said my doctor was running over an hour late—which they normally are in the VA system—but there was a psychologist down the hall if I’d like to talk to her. I thought, Well, why not?

I went down and met a nice lady psychologist, and we talked about various things. I explained I was not feeling right. She had a couple of questionnaires, and I did three or four short tests. She looked at comparisons on the computer and diagnosed me with PTSD. She had her boss, Dr. Mazzoni, come in, and he had some tests for me, too. He concurred with the psychologist on the PTSD diagnosis. He asked me to come back soon and to bring my wife. I asked him if I could bring my young son, and he said by all means. So Sandy and Matt and I returned for the next appointment and started discussing the diagnosis.

I said, “Before we get too far, I need to apologize to you because the other day you asked me a question, and I didn’t tell you the truth.” It was the whole thing about having suicidal thoughts and whether I had ever gone beyond plans. I had laid out the whole thing. It was pretty well planned out in my mind, exactly where the suicide was going to be, how I was going to do it. And there were times when I felt, “Today’s going to be the day. I just can’t do this anymore.”

The psychologist asked me why I didn’t go through with it. I looked at Sandy and Matt and said, “I couldn’t bring myself to think about leaving them with the mess to deal with. There’s a physical mess, there’s a mental mess, and there’s also the stigma that would reflect on her or would reflect on me even when I’m gone.” And I thought about all the guys on the Wall. I’m sure if they had had the opportunity, they would just as soon that their name wasn’t on the Wall. And with the honor that’s involved in that Wall, I didn’t want to go out that way. I didn’t want people saying, “I remember him, he shot himself back in . . .” I was starting to get a big monkey off my back.

Then he said, “Well, we’re going to get you back into mental health. There’s a VA clinic closer to where you live.” When we went there about three days later, we were assigned a caseworker. After Sandy and I had spent a couple of hours with him going through things, he said they’d get me assigned to a doctor. Of course, once I let the cat out of the bag and got out of denial, everything was tearful and emotional. You get the release.

Ready for a memorial service.

He asked if I’d heard of the Vet Center, and I hadn’t. He gave us a flyer for the one in San Jose, so we drove down to check it out. When you pull into the parking lot, there is a huge banner as you walk in the door that says, Welcome Home. I had a lump in my throat. It’s a quiet atmosphere, with comfortable furniture and the lights turned down. The director came out and invited us into her office. We started talking—and Sandy and I both fell apart.

Within the week I was assigned to a counselor, and Maria’s been my counselor there ever since. I never before felt like I had been welcomed home. I started seeing her and doing group sessions. I met a lot of guys. In the group sessions, we got comfortable sharing around the table with strangers. You’re not strangers for very long. At a certain point, I started to feel like I didn’t want to go anymore, because it was taking me out of my comfort zone. But driving to the Vet Center got easier again—I knew I was going to a safe place. I got that safe feeling about the Vet Center long before I ever did when I was going to mental health clinic.

Then one day Maria said, “You need to get a dog.” We’d talked about dogs that we’d had and especially our boxer, who had died. That dog had really gotten to be part of the family. She said, “You need to get another dog.” We weren’t ready yet, because we still lived in a small space. It wasn’t long after that good things started happening. We had discovered a home we could afford, but through Maria’s hard work, we found out we had a high credit score, so we could start looking for a nicer home in a nicer area. This was in 2011.

Tell me about the day you found Abbey.

We got her May 28, 2011.

How did you find her?

She was in an accidental litter of Great Dane pups in Morgan Hill. Our granddaughters had picked out a dog, and they wanted us to go with them. A lady trotted out this female, and all of these pups were running behind it. One little black pup kept coming over to us. When we brought her home, for the first couple weeks I thought we’d made a mistake because the dog was driving me a little bonkers.

How old was she when you brought her home?

Eight weeks. We named her Abbey. As she grew a little older, taking her on walks and getting used to having a puppy became easier. I thought I would be able to cope. When Abbey was about a year old, we were doing some puppy classes at PetSmart in Gilroy. Maria asked if we’d heard of the gal who trains dogs and veterans together.

When you had Abbey as a puppy, were you still seeing Maria?

Yes. I wasn’t able to take the dog with me, but Maria would always ask how Abbey was doing. The head of the Vet Center said absolutely no dogs, because it’s a small building. But Maria told me that if a service dog comes in, you have to let them in, by law. She showed me a news clipping from the Gilroy Dispatch about Mary Cortani and Operation Freedom Paws. I looked up OFP online and read all the information. Sandy and I talked about OFP, and I thought it was something I could do. We downloaded the form, filled it out, and sent it in.

In July 2012, we got called in to meet with Mary at OFP. As we were talking, Mary took Abbey off separately to see what her capabilities might be. When she came back, she said she thought Abbey and I would be fine in the program. We went over the information, what was expected, what I could expect, and the minimum training that would be required. We went back that Monday night and sat outside the first hour. Abbey was being a goofball. I had her on a short leash, but I didn’t have it adjusted right. Suddenly, I felt like my mind was made up: “This is not going to work. We can’t do this.” But in the second hour, Mary had us come inside to see what was going on. Things got better then.

She gave us a special vest with service dog patches so that out in public people would understand that Abbey was working for someone with a disability. Mary said, “Now when you’re out and about, you put the vest on and you start working with your dog.” I thought, Oh God, this is going to be like boot camp. After that first class, I told Sandy I thought I could go by myself, just Abbey and I. That’s what we did, and it worked out. Of course, there were frustrating moments, but that’s true for every new person who comes into the program. But it gets better and better. Twenty eyes are watching to make sure you’re all right all the time. I go back to that first Monday I met Mary, when she told me before I went out the door, “I just want you to know that as long as you’re here, I have your six.” I don’t know there’s ever been the occasion that she hasn’t.

Miss Abbey at 6 weeks when she chose me.

In the first year, I only missed a couple of classes. I started going on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Saturdays. I also started stepping out of my comfort zone a bit, making some presentations for OFP. The first one was at Santa Clara County Reads. I made a comparison to show how I got to where I am today. Throughout my life I’ve always had a shoebox for keepsakes. At one time, it was baseball cards and track medals, or some fancy key chain, or some little thing I’d made. You keep adding things to that box, and every now and then you go back and look at the stuff. Well, the box got bigger, and with all the Vietnam experience and whatnot, I got to the point where I felt like, especially after being at the Wall, that I couldn’t get all my stuff back in the box. I shared about being at the Wall and how that led to realizing that I needed to get help. That night, I thought, OK, we got through that, and I don’t ever want to do that again. But then the next week it was the Gilroy library.

How does Abbey help?

The main thing is being able to get out of the house and go places. I don’t feel like I’m trapped all the time. The more you do, the better you get, like anything else. It used to be a task: “I’ve got to get her ready. I’ve got to drive down here. I’ve got to make sure she goes potty before we go in the door. I’ve got to make sure her nose is not touching this or that, or that she’s not bothering somebody walking by, or that she’s not looking in their grocery carts.” It goes from being totally aware of that to a comfortable level of knowing that while you still keep an eye on the dog, you know that she’s most likely not going to do something wrong.

I’ve only had one situation where I was totally at fault, and I wasn’t listening to my dog. I got in trouble at the OFP grand opening in September 2014. We’d rushed around and had class, and I tried to do stuff at the last minute to get things ready. I was helping with the barbecue. It was hot, and Abbey was pulling on me, and my neck started hurting because she was pulling so hard on the leash. I felt myself getting mad, so I handed the leash to Sandy and told her to hold Abbey for a few minutes. I went back over to the hot grill and I bet it wasn’t more than forty-five seconds before I had to go sit down. I was starting to lose it.

By “losing it,” do you mean you were going to pass out?

I started feeling like I was going away . . . Mary asked if she could rub my neck. I told her it was my shoulders—I had to take off the rucksack.

I was back in Vietnam that quick. I said, “I just can’t hold it up anymore. I need to lie down.” She got a blanket and a pillow, and I lay down in the shade. I was out for about fifteen minutes. Then, as I was lying there in the shade, I realized where I was. I was probably physically tired from the event—tired probably before I ever started the day. It scared me because it happened so fast.

Abbey knew it. It was the first time she had alerted me to anything. I didn’t know she was alerting me. It scared me enough that I made a promise to myself and to Abbey that I’d never question her again. I mean, I was back in Vietnam, and all I could think about was, I have to get this rucksack off.

That point was really driven home. For instance, when I’ve had the flu, Abbey would constantly check on me. If I get to the point where I have to sit down, she’s with me. She’ll nudge my arm. She’ll come over and lick my arm if I’m sitting in a chair. When I open my eyes after dozing, she’s lying on the loveseat, watching me. She’s turned out to be a real battle buddy, so to speak. She’s part of me now. She’s part of the family.

If that kind of thing had happened two years earlier, I wouldn’t have come out of it so fast. But within a few minutes I was aware of my situation, thanks to Abbey.

She was pulling on you to alert you.

Yes, Abbey was pulling me away from the heat and telling me to sit down. Heat is one of my top five my triggers. I learned a big lesson that day: Listen to my dog.

At night, Abbey usually goes to bed before I do. She’ll go into her big kennel in the corner right by my nightstand. But she doesn’t fall to sleep until I sit on the edge of the bed ready to get in. I talk to her every night and read her my little meditation text, where you take yourself to your favorite place. I don’t know if it’s the tone of my voice, but she’ll lie there looking at me. And by the time I get under the covers, she’s asleep.

Sandy and I are to the point now where I think our grasp of my dog and the management of PTSD and triggers are really the main part of what Abbey and I are doing together. Abbey and I have been going out lately. For example, we went to the VFW in Gilroy and manned a table for three or four hours on veterans resources. That Sunday, we drove over to Livermore and met Kevin for a veterans appreciation dinner. Going off and doing that, I had anxiety. It was more about being away from Sandy and thinking she might need me at home. But I had a certain amount of comfort because I had my dog and I could touch her.

Sandy, Abbey and I visiting the Corbridges.

Does Abbey help with anger issues?

She prevents me from getting into those situations where I get upset about things. The anger doesn’t linger on like it used to. I might get road rage—that’s one thing we’ve been talking about in class. In my therapy group I shared a little conversation I had with a CHP officer one day about serious road rage. The story wasn’t about getting out of the car and getting in a fight, but about how that road rage could’ve resulted in a terrible accident. Now, I have my dog right here, and I can just reach over the seat and touch her.

So just being able to touch Abbey can calm you?

She brings me back to the here and now. She keeps me right there, right now. I don’t have time to be thinking about something I have no control over. When you’re able to do that, your blood pressure’s not going up. Your anxiety’s not getting out of control. There’s a calming effect that comes with the dog, once you really get into that phase where you know that the dog is another tool in the tool belt. Abbey is there to take me through those moments and let me stop and think about why something is bothering me—about the real reasons something is bothering me.

I am just so thankful. It’s like being free again. I know I’m not trapped. To be able to come out of those feelings of helplessness and anger is just—you can’t put dollar signs on it.

It’s amazing how that short time at war, out of all my years on earth, has consumed so much of my life. It’s defined my life. It’s been a long ordeal. And I’m still working on it.

#

RESOURCES | INFORMATION:

- Service dog training provided by Operation Freedom Paws

- ADA Requirements: Service Animals

- ADA Frequently Asked Questions

- Photographs courtesy Denny McLaughlin.